Today, I’ll be posting about the U.S. elite college admissions review process and strategies to increase your chances of acceptance.

There’s a question that many students and parents often ask:

“If a friend from my high school—who seems slightly stronger than I am—applies to the same college, should I give up applying there?”

To answer this, let’s take a close look at how the admissions process works at prestigious U.S. universities, and what strategies can help you improve your odds.

The First Gate in the U.S. College Admissions Review

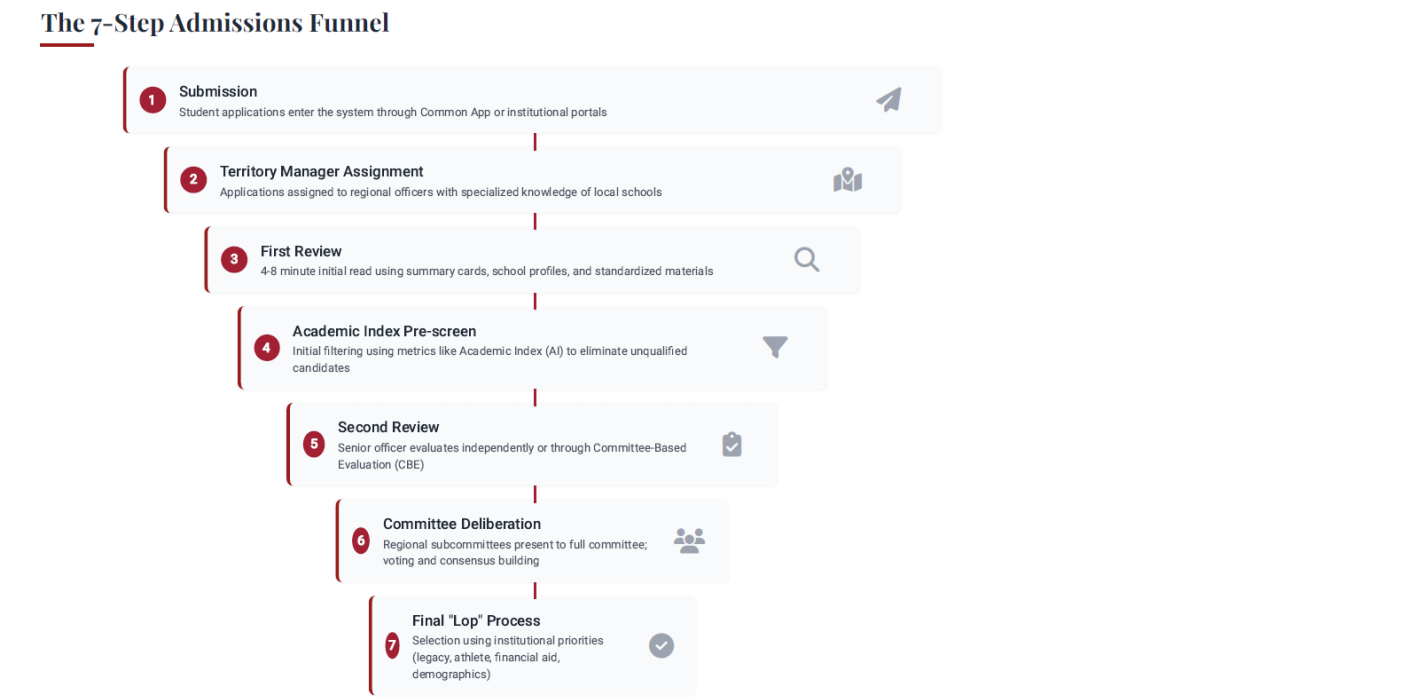

With tens of thousands of applicants, the admissions process at U.S. universities is highly complex.

Once you submit your application, it is assigned to a regional officer, called a First Reader, who may spend anywhere from 8 to 20 minutes—or sometimes as little as 4 minutes—reviewing a single application.

Within that short time, they prepare a Summary Card to capture the key points of your file.

Some universities also use an AI (Academic Index) to pre-screen applicants.

While certain schools will reject candidates purely based on metrics like GPA and standardized test scores, most top-tier universities are known not to eliminate applicants in such a mechanical way.

After the First Reader’s review, the application goes to a Second Reader, and then to the Committee for a vote to decide final admits.

At the very end, the Lop Process is used to adjust the final number of admits.

The Core Strategy: Capturing the First Reader’s Attention

As mentioned earlier, the First Reader—the regional admissions officer—often reviews an application in just 8–20 minutes, sometimes as little as 4 minutes.

The reason is clear:

-

They may read 100–200 applications in a single day.

-

Over the course of a season, they may review more than 1,500 applicants alone.

With such a massive volume, it’s virtually impossible for them to examine every file in deep detail.

So how should we prepare?

-

Include standout activities or a strong message on the very first page.

In that short time, you need to give the impression: “This student has a clear strength.” That’s what will get you through the first gate. -

Connect your scattered activities.

The Reader won’t have time to connect the dots for you—your activities need to be organized into a coherent narrative ahead of time.

If you fail to win over the First Reader, your application may never make it to the Committee stage—meaning you’ll lose the chance to have it read and discussed in detail.

To summarize the whole process:

U.S. colleges receive tens of thousands of applications each year, submitted via the Common App, Coalition App, or the school’s own application system.

First review is conducted by the regional officer—also known as the Territory Manager or First Reader—who does a very quick evaluation. Then the Second Reader reviews the file independently or as part of a Committee-Based Evaluation (CBE) system before it moves forward. (More on CBE later.)

Next, the application goes to a Subcommittee, and then to the Full Committee, where the final admit decision is made through a vote. One step many parents don’t know about is the Lop Process—which I will explain later.

Because Readers have so many files to get through, the time spent on each is getting shorter and shorter. More time and discussion are reserved only for the most competitive applications. If your file doesn’t make it to the Committee stage, it may never be read closely or seriously considered.

Some schools also conduct pre-screening using GPA and standardized test scores (SAT, ACT, etc.). Those who don’t meet the threshold are eliminated before reaching the Committee.

At the very final stage, another filtering occurs, where factors such as Legacy status, Athlete recruitment, Financial Aid status, and Race can influence the final decision.

Two Evaluation Models: Single Evaluator vs. CBE

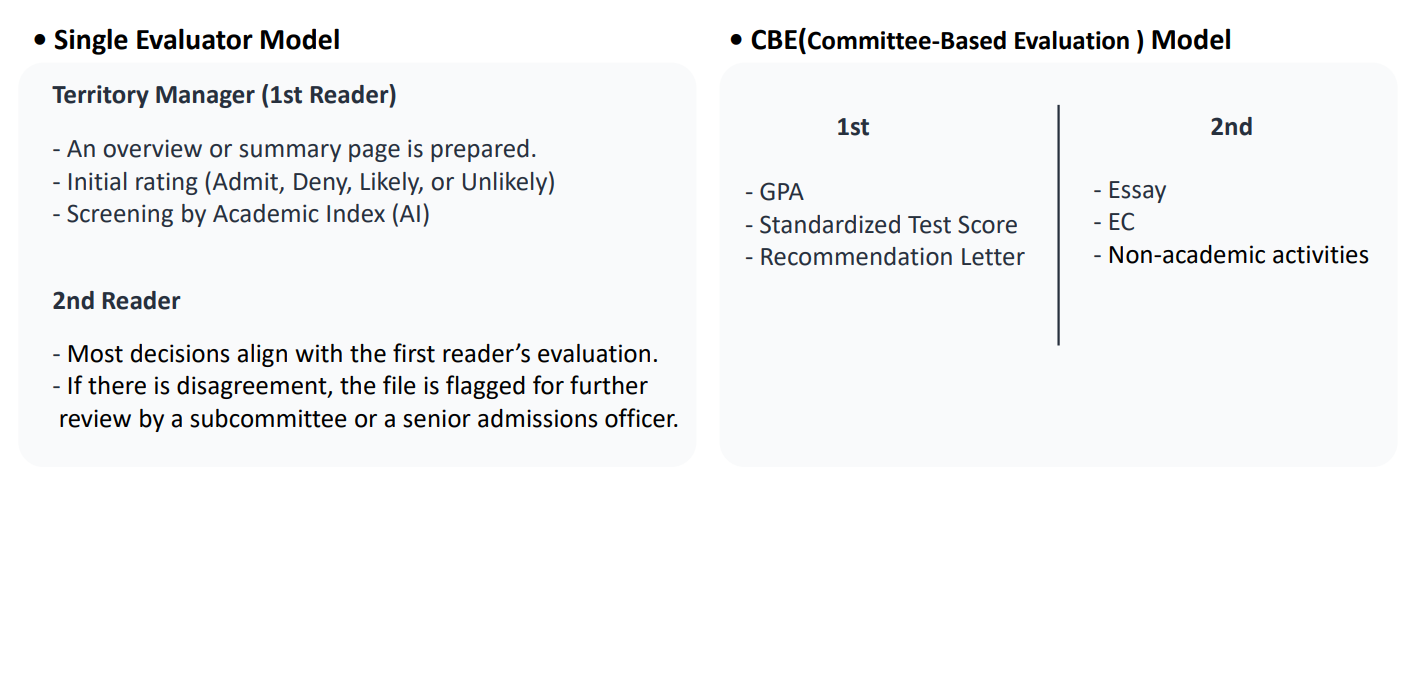

There are two main models for how First and Second Readers evaluate applications:

-

Single Evaluator Model: Both Readers independently review the entire file in full. The First Reader makes an initial recommendation (“admit” or “deny”), and the Second Reader usually agrees. If they disagree, the file is sent to a more senior officer or to a Subcommittee for a decision.

-

CBE (Committee-Based Evaluation) Model: The First and Second Reader split responsibilities. For example, one might focus on GPA, test scores, and recommendation letters, while the other reviews essays, extracurriculars, and non-academic activities. Their combined evaluations are then sent to the Committee. Schools like U Penn, Caltech, Emory, and Swarthmore use this model.

Applications that pass both Readers and show high admit potential move to the Subcommittee stage.

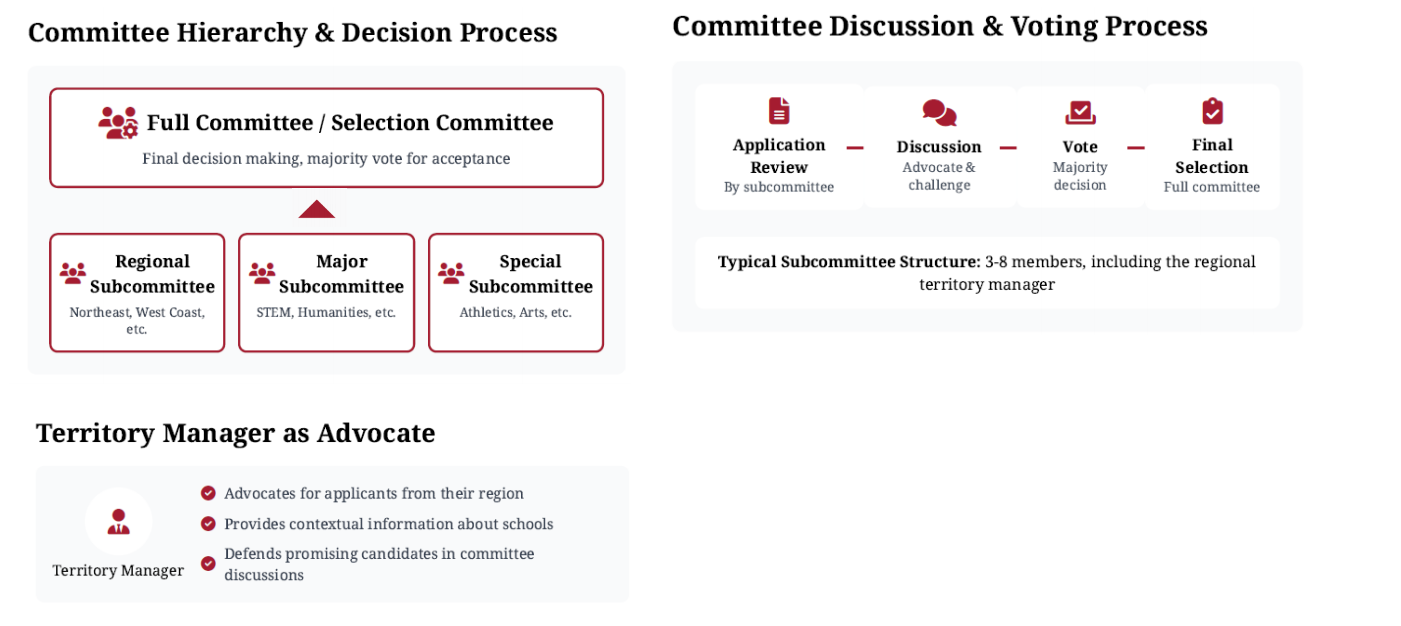

The Role of Subcommittees

Subcommittees are not a single step before the Full Committee—multiple subcommittees review applicants in layers.

There are generally three types, each with 3–8 members:

-

Regional Subcommittee: Evaluates based on the applicant’s geographic background.

-

Major Subcommittee: Focuses on the fit and preparation for the intended major.

-

Special Subcommittee: Evaluates talent-based applicants—arts, athletics, or other special skills.

The First Reader is part of these subcommittees, acting as the advocate and defender of the applicant.

Two Ways to Reach the Full Committee

-

Applicants deemed competitive in the Subcommittee are sent to the Full Committee for a final vote.

-

Applicants with borderline cases are also sent to the Full Committee for a majority vote decision.

The Full Committee is composed of more experienced members, ensuring rigorous and objective judgment.

Because every applicant is reviewed by multiple subcommittees and leaders, it’s very difficult for one person’s personal recommendation to guarantee admission. The process is designed for fairness and multi-angle evaluation.

Exceptions and the Final Gate: The Lop Process

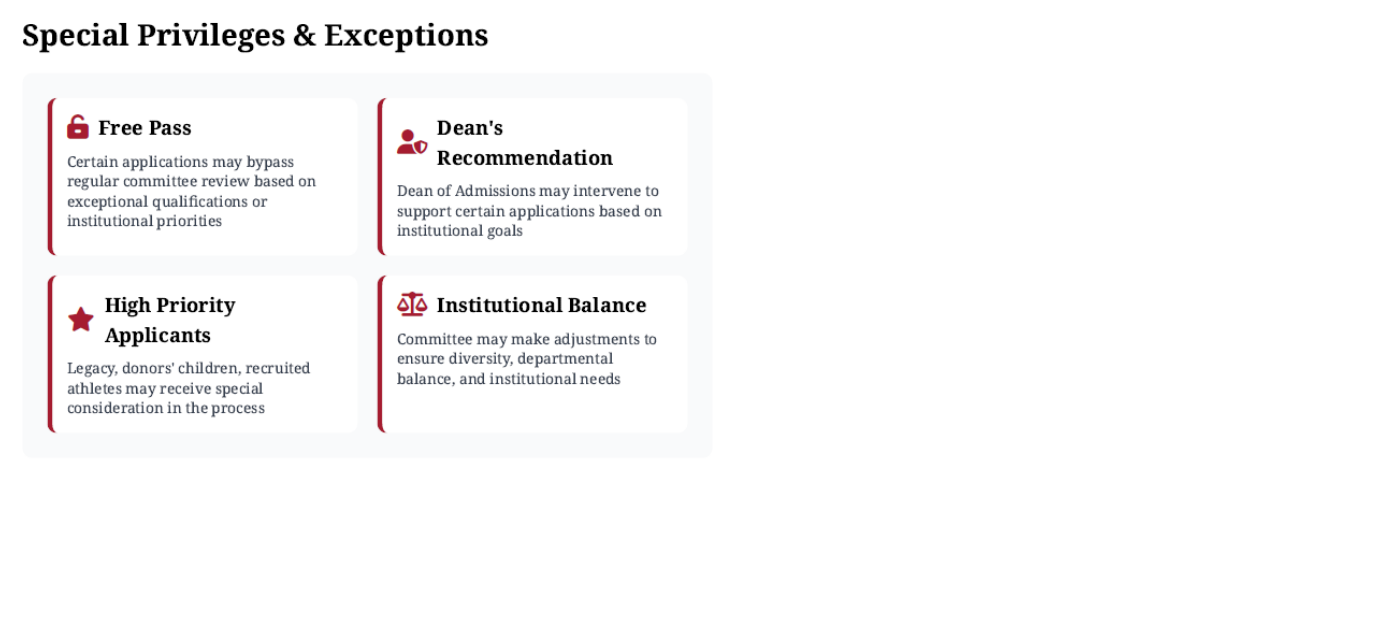

Some students bypass the standard process entirely:

-

Free Pass: Students from certain high schools, or those with exceptional results in competitions like the Olympiad or ISEF, may be admitted without considering other factors.

-

Dean’s Recommendation: Directly recommended by the dean—virtually guaranteed admission.

-

High Priority Applicants: Recruited athletes, children of major donors, or legacies have a clear advantage.

-

Institutional Balance: Race or ethnicity may be considered to balance the composition of the class.

These exceptions are rare. Most students go through the standard process described above. Many top schools, including Harvard, use category-based scoring systems that rate both quantitative and qualitative factors.

Harvard’s Evaluation System

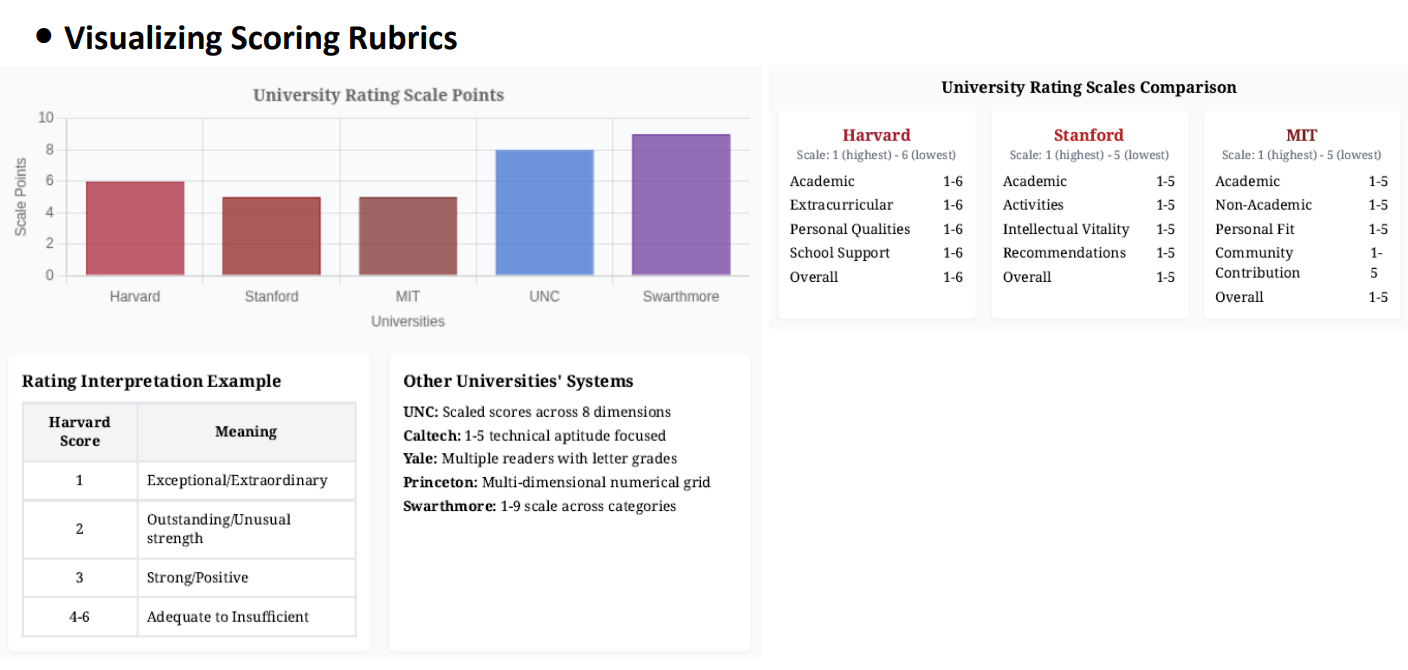

Harvard scores applicants in these categories:

-

Academic

-

Extracurriculars

-

Personal Qualities

-

School Support (recommendations, counselor input)

-

Overall

Each category is scored on a 1–6 scale:

| Rating | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 1 | Exceptional at the national level |

| 2 | Excellent at the state level |

| 3 | Strong at the school level or with consistent activity |

| 4–6 | Minimal or no significant activity |

For example, a consistent school-level leader might earn a 3 or 3+, while someone with little activity would be rated 4–6.

Other schools’ scales vary:

-

Harvard: 1–6

-

Stanford / MIT: 1–5

-

UNC: 1–8

-

Swarthmore: 1–9

The structure is similar: category-based scoring → average score calculation. (Note: “ratings” aren’t the official term used in admissions, but help explain the concept.)

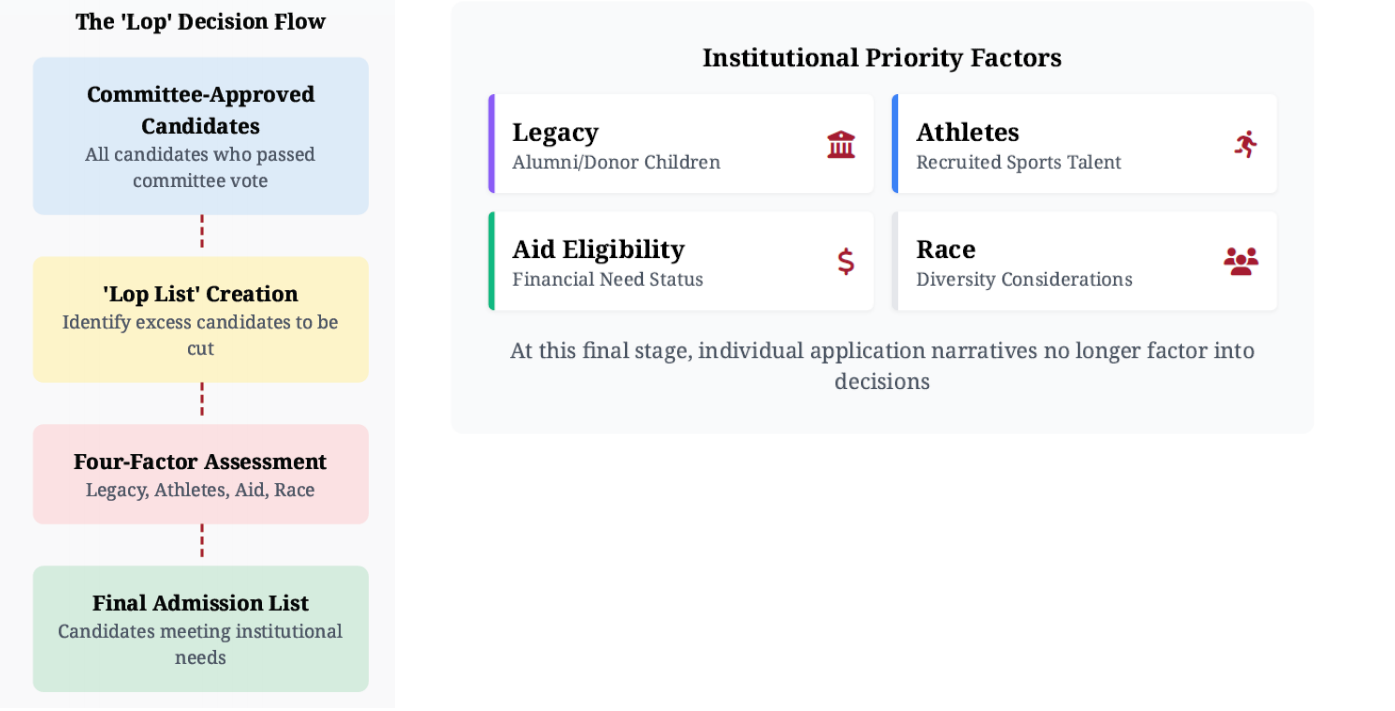

If, after all review stages, the number of admitted students exceeds the target, the Lop Decision Flow is applied.

At this stage, factors like GPA, test scores, essays, and activities are largely ignored. Instead, only these are considered:

-

Legacy

-

Aid Eligibility

-

Athlete status

-

Race

Sometimes students who made it all the way to the verge of admission are rejected—not due to shortcomings in their activities, but because of this final process.

Back to the First Question

So, should you avoid applying if a stronger student from your high school applies to the same college?

The answer is “YES.”

At that point, the admissions officer isn’t asking, “Is this student strong?” but rather, “Is this the strongest applicant from this high school this year?”

If a peer is likely to be judged “the top applicant” from your school, they will probably be favored.

Most elite colleges have regional or high school quotas. Schools like Harvard and Princeton tend to admit about the same number of students from a given region or high school each year, with little variation.

Some universities, like MIT or Yale, publicly state they have no regional quotas. But admit data still shows they tend to select a similar number of students from each school annually.

That’s why knowing and managing this reality is important. High schools should share application plans transparently among students and strategically spread out applications to top colleges to maximize everyone’s chances.

I’ll return in my next post with more useful information.

For Digital SAT prep, I recommend ett-test.com.

It’s the only place where you can find video explanations for every single problem—resources you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you.

committee

application